In my last post I gave an overview of how the fake news we see now has developed over centuries. In this one, I’ll focus on the fake news that has been widely circulated over the past couple of years, specifically focusing on Covid-19 and the Ukraine War. These are issues that are still ongoing now, and generate vast quantities of misinformation filled reports. The more turbulent the state of our societies, the more we glue ourselves to news sources and social media. We have constant 24 hour access to information, but is this knowledge making us feel safer? Calmer? Or does it generate mass hysteria, making it harder to spot what’s real and what’s not?

Anxiety and Paranoia lead to Fake News

With the war in Ukraine, we can see an example of a state using fake news and misinformation for its own benefit. Research from the UK government found a campaign of disinformation coming from Russian “troll factories.” Their aim is to sway opinion towards Russia and against Ukraine, recruit sympathisers and attack foreign politicians who speak out against them. The study found them to be operating across major social media platforms. Of course, the Kremlin denies the existence of this campaign.

But the fake news is also coming from other sources. Earlier in the year, there was a big problem on a major social media platform with people posting videos and livestreams, claiming to show the conflict in Ukraine. But, the footage came from other conflicts, movies or even video games. The point of this? That platform has a “gifting” system users can use to send money to creators. Those posting the videos seek sympathy and request money from those who just want to help in this terrible situation.

Both of these sources of fake news prey on the public’s anxious drive for more and more information. Topics such as the pandemic and the Ukraine war and devastating but fascinating, and we compulsively consume and spread as much information as we can about them, often overlooking reality in favour of sensationalism. This is why fake news works so well.

Even out in the real world you can’t escape misinformation from Social Media

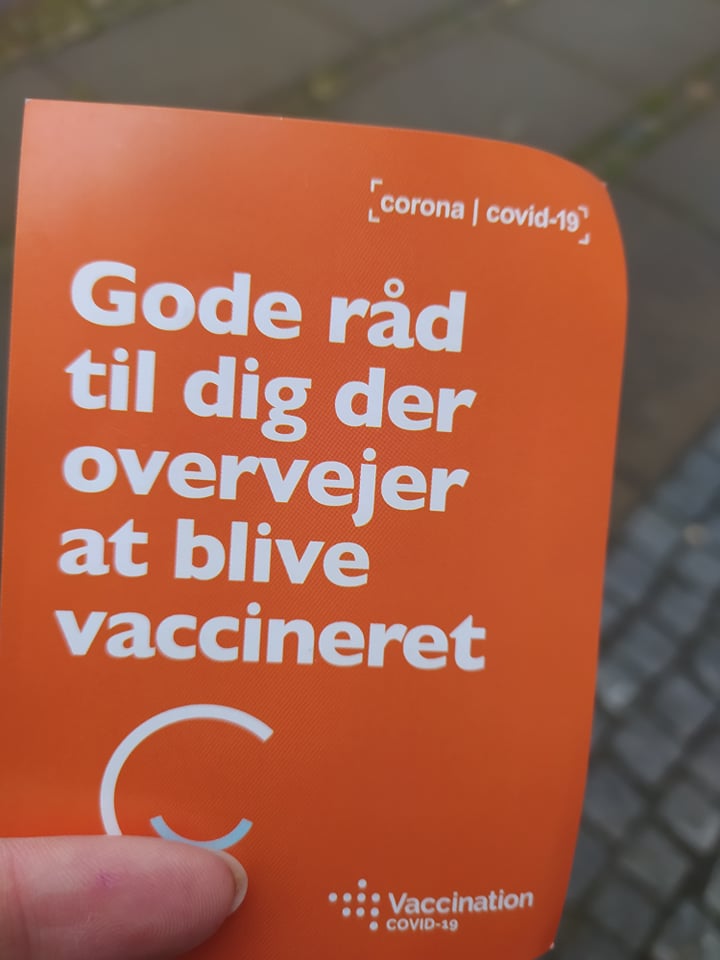

The two images below show a flyer I personally received in my postbox late last year. I live in Denmark, where the Covid-19 vaccine uptake amongst the population has been very high (85% of the population has at least 1 dose), and ‘anti-vax’ protesting minimal. So, I was fairly shocked to receive this. It uses the same Covid-19 logos as the national health services, attempting to look like an official document. However, if you follow the QR codes on the back, they lead to TikToks, YouTube videos and articles filled with vaccine misinformation from individuals claiming to be medical professionals.

Because of my age and how I spend my time online, it wasn’t hard for me to spot this as anti-vax propaganda. But, I can see how others could fall for it, for example if you have less experience discerning fake news. This is especially true if it comes to you from outside social media. Or, perhaps you’re a recent foreign resident in Denmark, such as myself. We aren’t as familiar with the health system or language. A flyer like this could lead to some serious confusion and have potentially lethal consequences.

How are we combating Fake News?

Last week, the European Commission strengthened their Code of Practice on disinformation, with signatories including major social media platforms and tech companies. The timing is related to the fake news weaponised by Russia to manipulate opinion and attack democracy, but will have a wider, more general benefit too. The aim is also to limit the possibilities to monetize fake news, removing the incentive to create and spread it. Companies could be hit with large fines, or even a ban from the EU market, if they fail to adequately protect their users from fake news.

Many social media platforms already flag misinformation they find, or remove it altogether. However, so far this hasn’t been enough. The rate at which platforms do this must increase with the development of fact-checking tools. Additionally, as well as labelling potential fake news as such, platforms will apply “indicators of trustworthiness” to independently verified pieces of news. Then, social media users can be certain of the accuracy of the knowledge they take in. Companies will have to give reports of implementation to the Commission at the beginning of 2023, so we’ll see the progress then.

So that’s the present, but where are we going from here?

In the final post of my Fake News series, I’ll write about the possible futures we face with fake news.