My Tiktok feed is probably pretty standard: book recommendations, cooking videos, MANY cats. Mind-numbing but generally harmless. Interspersed throughout are a smattering of mental health support videos. Some share their own experiences of lifestyle and treatment. Others discuss their concerns and struggles. It’s people generally normalising mental health problems. I can’t argue that this isn’t a good thing. De-stigmatising mental health is vitally important, and it’s admirable that younger generations are more open to that. But (big but), over the past couple of years mainstream social media has strayed into a different kind of mental health content. So far social media “psychiatrists” have diagnosed me with autism, ADHD, PTSD, depression, anxiety, etc. etc. Videos listing “symptoms” you can diagnose yourself with are wildly popular. What’s even worse are videos making these disorders seem like quirky character traits, rather than life-ruining conditions that people suffer from. How did we get here?

Self-Diagnosis is far too easy on the internet.

Ever felt a twinge in your chest? A headache that’s gone on a bit too long? Did you Google your symptoms? There’s a reason doctors generally advise against this. The nature of the internet means that the results you get will be the most sensational, and the most dramatic. Your sore toe probably isn’t an ultra rare wasting disease that’ll kill you in 2 hours, but an official looking medical website may say it is. Humans are very susceptible to misinformation, especially when under stress. The internet has gifted us a wealth of knowledge at our fingertips, but that doesn’t mean we know how to accurately apply that knowledge.

Now imagine a teenager in Covid lockdown. Stuck in their bedroom with nothing to distract them from the horrors outside except their phones. Their education is interrupted, they can’t see their friends, their mental health is plummeting. But, they start coming across posts describing exactly how they’re feeling, and they relate to them. They give them a name for what’s happening to them, and a community to join. The content creator claims to be an expert, or to have the condition themselves. They diagnose themselves, because it seems obvious that it’s correct. But with no actual health professional directly involved, misdiagnosis and mistreatment is likely, and their mental health will just get worse.

There are many barriers in place when trying to access mental health support.

The obvious answer would be to see a doctor or psychiatrist, and get a proper diagnosis. Unfortunately, in many places this is extremely difficult, or even impossible. Countries with public mental healthcare are experiencing massive pressures as the volume of patients skyrockets. Or, in countries where healthcare is paid for through insurance or out-of-pocket, a cost of living crisis is making healthcare unaffordable. Many countries’ healthcare systems are still recovering from the pandemic, and there is little to no investment going into mental health. Combined with the massive mental health impact of the pandemic, everyone is struggling.

Another issue is the openness of the person struggling with mental health problems, or their family’s, to seek help. A lot of these are young people who may rely on parents and guardians to get them the help they need. What can they do if they’re dismissed or stigmatised? Or if they have no one to get help for them? And what if they choose to believe the ‘influencer’ psychiatrist, who they feel trust and familiarity towards, over healthcare professionals: strangers who may not tell them what they want to hear? These are all complicated situations to navigate.

What do social media personalities gain from spreading mental health misinformation?

The obvious reason is clout and money for influencers. The number of young people with mental health problems is astronomical, not to mention feelings of depression and anxiety can just be a part of growing up. This means that sensationalising mental health problems to make content can get you a loyal audience fast. An audience who you have a deep level of trust with, having shared discussions of trauma, healing and self-care.

Then there are the for-profit health organisations who mis- and over-diagnose patients. I’m not going to start a ‘Big Pharma is out to get you!’ rant, but it’s a recognised issue that not all healthcare authorities have a patient’s best interests at heart. For example, earlier this year the BBC’s Panorama exposed private ADHD clinics who were telling patients they had the condition when they didn’t, prescribing them powerful drugs, and subsequently taking vast sums of money from them and the NHS to do so. ADHD is the most “popular” mental health condition on social media at the moment, so the pool of victims seeking diagnoses is ever growing.

And why is it dangerous?

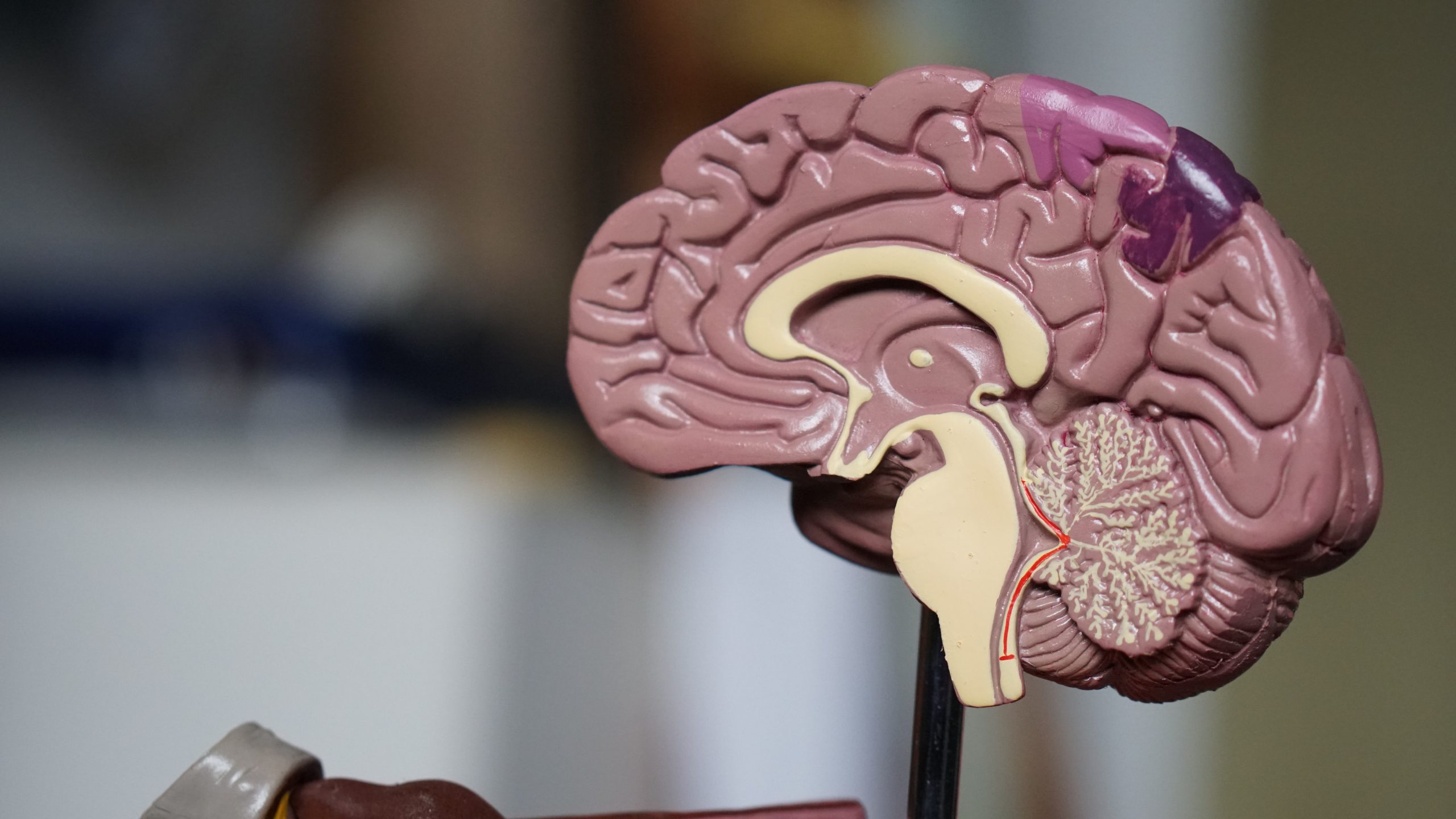

Other than being a potential victim of a scam, there are some other concerns. One had a rather dramatic example not long ago with the rise in ‘Tiktok Tics’. This article from The New York Times compares the spread of mental health disorders through social media to famous historical outbreaks of “mass hysteria”, such as the Loudon Possessions. A group under stress can spread psychological disorders amongst themselves, and teens on social media are certainly stressed. This is how during and soon after Covid lockdowns some young people started showing Tourette’s -like symptoms, without actually having the disorder. By watching influencers on social media with tics and having a history of other mental health problems, a wave of young people started suffering from them too. However, after returning to normal post-lockdown life and spending less time on social media, most of them made full recoveries.

And what of the people who really do suffer from properly diagnosed psychological disorders? They have to watch healthy people label their normal, human, less-desirable psychological quirks (forgetfulness, shyness, talkativeness, clumsiness, and so on…) as severe disorders that make them special and included in a community. Keven Devine is a creator on Tiktok who calls out other content creators spreading misinformation about ADHD, which he suffers from. His videos are great examples of what I’ve described in this article.

If you suspect that you are having mental health difficulties…

It is vitally important to get a professional and trusted opinion. In most cases your primary care physician would be the place to start, but those in school/university settings may have on-site services available to help. I know I said earlier that these services aren’t always easy to access, but it’s important to be persistent and stay on waiting lists. For those with financial constraints, there are many charities available for mental health support that you can Google for your local area. This website has the contact details for help services worldwide.

In addition to this, it’s important to not get sucked into the world of social media psychiatry and make yourself worse. What can seem like support may just be romanticising pain and suffering, making symptoms linger and in some cases introducing new ones. So many studies have shown that a reduction in social media use improves mental health. For your own sake, take a break.